How to Change a Culture

When we humans took over the world, it was for one reason and one reason only — culture. But the work isn’t done yet.

When we humans took over the world, it wasn’t because we were the fastest or strongest. We won for one reason and one reason only — culture. But the work isn’t done yet.

What is Culture?

Culture doesn’t have one easy definition, so I’ll share mine: Culture is what members of a group expect of one another. (Experts call these expectations norms.)

These groups can take many forms. Just as cities, companies, and civilizations can have cultures, so can rooms and families. All that truly matters is proximity and a little bit of shared identity.

The expectations are double-edged — they cover both what we expect others to do and what we expect others to expect of us. A lot of miscommunication can happen in those gaps.

Since we’re wired for community, we usually want to meet each others’ expectations. It requires extraordinary mental and emotional effort to defy our culture — so much that we usually only consider the options our culture provides.

For every choice we make, conscious or unconscious, we have options. Some options are obvious, and some aren’t even visible until we change our story or environmental factors.

Because of our social wiring, culture is the single most influential environmental factor. This means that our culture influences every choice we make. Culture makes our default menu of options.

What we expect of each other

When talking about policy, political theorists call this menu of options the Overton window. Overton theorized that every government had a range of ideas that would be considered politically viable, and anything outside this window is preposterous.

The window moves all the time. In the US in 2016, Bernie Sanders moved Medicare For All into the window, and in 2020 every Democratic nominee was expected to have an answer for it. On the other side of the aisle, Donald Trump moved explicit racism into the Overton window in 2016 and a Confederate flag flew in the Capitol in 2021.

But the idea’s useful beyond politics. In any group you’re in, there will be unique expectations from and for the people around you. Think of these as the rules — maybe they’re unwritten, but they’re there.

Example: You’re in a meeting at your new job. You’re quietly tracking the whole time who talks when, who’s wearing what, who disagrees and how, and who is multi-tasking. Do people casually curse? Do people contradict the boss? Everything that happens might happen again. Anything that doesn’t won’t be expected, especially if you haven’t seen it anywhere before.

In any scenario, whether you feel it or not, you’re mapping the Overton window. The biggest clues are when lines are crossed. “Okay, so we don’t say that word.” “Okay, that person gets to be wrong.” “Oh, maybe I can wear a graphic tee.”

But we’re not just here to map it. We’re here to change it.

Sculpting Culture

With every action anybody takes, the people around them have a choice to accept it or reject it. When something is successfully accepted, it becomes expected behavior that is likely to succeed again. When something is successfully rejected, it becomes unexpected.

An example: You’re at a party, and you make a joke. Everyone laughs. Acceptance. Someone makes fun of you. Everyone laughs, including you. Acceptance. Someone makes fun of your family. You don’t laugh, so no one laughs. Rejection. In this group, you have established the expectation that it’s okay to make fun of each other, but not each other’s families. Just like that, you’ve removed a bad option from others in this culture.

(Note that this is a true peer group, so there’s no power dynamics throwing the balance. In reality there are almost always power dynamics, but we’ll get to that later.)

What I described above is a simple example of social conditioning, itself a subset of operant conditioning. Since our brain chemistry (a.k.a. nature) is so community-oriented, conditioning (a.k.a. nurture) explains most group behavior.

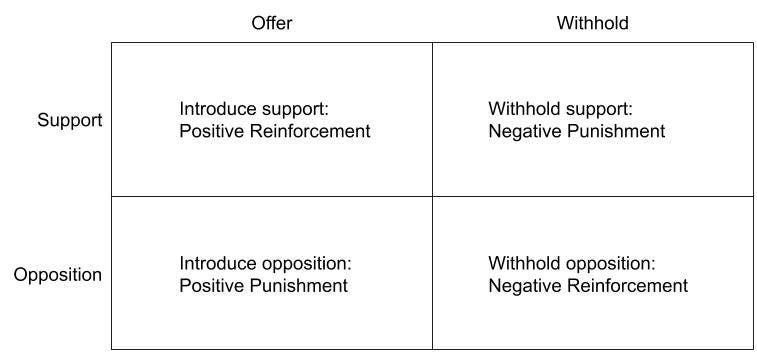

The details of conditioning are complex, but it all comes down to reinforcement and punishment — carrots and sticks.

Carrots:

Positive reinforcement: Rewarding through action. Someone makes a joke and everyone laughs, rewarding the humor.

Negative reinforcement: Rewarding without action. Someone says something cruel and you say nothing, rewarding the cruelty.

Sticks:

Positive punishment: Discouraging through action. Someone says something cruel and you challenge them, discouraging the cruelty.

Negative punishment: Discouraging without action. Someone says something funny and you don’t laugh, discouraging the humor.

When used in response to boundary-pushing behavior, these tools can be used to shift an Overton window. But they’ll help with any behavior — and all behavior influences culture. They’ll impact every observer in the group, not just the individual you’re responding to. In short:

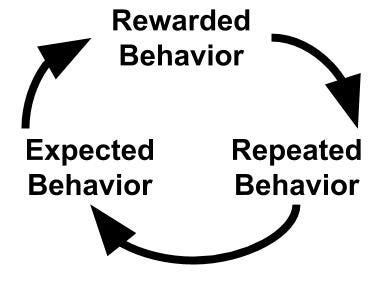

What gets rewarded gets repeated.

What is repeated becomes expected.

What is expected gets rewarded.

This feedback loop happens in every culture, however subtly, and is responsible for a lot of good and a lot of evil. If you can fix one part of this loop, you can have exponential impact.

This method of cultural change requires courage and something to react to. If you have no power in a scenario, it’ll require even more courage because it may not work and may itself be punished.

This next method needs nothing but courage.

Stretching Culture

Carrots and sticks define what does and doesn’t get rewarded, but someone has to take the action in the first place. A culture can’t normalize something that has never happened before. If something is missing from a culture, the best thing you can do is introduce it yourself.

Example: You’re in a dull meeting, and you make a joke. Everyone laughs. Acceptance. Someone else makes a joke. Everyone laughs, including you. Acceptance. In this group, you’ve helped establish that humor is accepted.

This is sometimes easier said than done, especially in unfamiliar groups. As we’ll cover later, power makes it a whole lot easier, but is not necessary. What you’re doing here is testing the boundaries of the group’s Overton window. It is entirely possible the group will respond with a stick.

That’s why courage is necessary.

In groups with long enough histories, almost everything has been tried at least once. If something isn’t in the Overton window, it’s because it’s been punished before. So you’re taking a risk where others have been burned before. How are you going to pull it off?

Beginner’s luck — This strategy works best when you’re new to a situation or an unknown quantity in some other way (maybe you have a reputation you can leverage?). Even if you have strong reason to believe something will not be accepted, it’s still worth a try. If it’s accepted, no matter why it’s accepted, you’ve blazed a trail. “Hi, I’m Josh, my pronouns are he/him. ”

Forgiveness beats permission — When in doubt, just do the thing. This might cost you some cachet for big moves, but even little moves like asking hard questions, testing norms, or challenging leadership can fall into this category. “Happy to be here. I’m going to keep my camera off today.”

These are just a few examples. The common theme here is that you’re testing boundaries while shielding yourself in some way. This shielding is important — if your action is punished, that will reinforce the edges of the Overton window you’re trying to change.

When you’re stretching what a culture will accept, you want to pile up as much support as you can to make sure the new behavior will be accepted.

The best way to ensure success is with power. Don’t worry though — you might have more power than you think.

How Power Fits In

If you haven’t yet, I recommend that you check out How to Know and Build Your Power, in which I explain the basic mechanics of power. To recap:

Your power is others’ belief, or expectation, that it will help them if you get what you want.

This belief is based on their trust that you can be expected to fulfill your offers and threats, or conditional promises.

This trust is powered by leverage —solid evidence or a reputation that proves you can and will do what you say you’ll do.

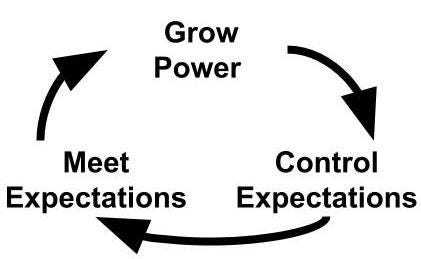

Note that expectations play a major part in power dynamics, just as they do in cultures. Cultures are powered by our expectations of each other, so powerful people both help set the expectations and are expected to meet them.

Different cultures generate and distribute power in different ways, but one important contributor in our culture is privilege, like my cishet white male privilege.

Privilege is a kind of leverage — it means society will do more to support me than it does others. This makes it easier for me to do what I say I’ll do, which people know when they’re subconsciously trying to determine how much power I might have.

Power comes from other places too — a title at a job, age in a family, and overall reliability. There’s a feedback loop here too. The more power you have, the easier it is to keep the promises that cement your power.

Let’s look at what happens in a social group where you have no power.

An example: Someone makes fun of your family. You don’t laugh, but everyone else laughs. Acceptance of the joke. This group has established the expectation that it’s okay to make fun of your family. Yikes.

That’s a wildly different scenario than what we discussed earlier, and a much less friendly one. What was different? Simply, the group did not view your expectations to be as important as those of the person who laughed at you. This person has more power than you do.

An example: The president and I both spend our days walking around and talking to people. That’s all. The individual actions, stripped of the trappings of power, are not wildly different. The difference is that his words can influence and control significant leverage (specifically, violence and money) because of his role.

Power adds weight to the someone’s expectations, and remember, culture is just our expectations for each other. So powerful people have the easiest time shaping culture. But even with very little power, you can still stretch a culture:

Aggressive humility — Pad your message or boundary-testing in politeness and agreeability, and people might not even notice that the window is shifting. One way to do this, especially when managing up, is by weaponizing an active listening technique: paraphrase what they’ve said back to them while adding your new message. If you get this right, they’ll think your idea was theirs. “Let me make sure I’m hearing you right — the team is burnt out and (new idea) the deadlines needs to move?”

Stack the deck — If you know you have an opportunity to test the window coming up, it helps to privately build consensus beforehand. Since every group has a different culture, different environments allow for different actions. If you get agreement from almost everyone in the room, you can overwhelm almost any power. Even a CEO can find themselves outside the Overton window if you play your cards right. “I think we all agree that this isn’t working.”

And remember the feedback loop? When you show control of the window, you show power, which gives you more control of the window and more power. For more ideas on growing power, check out that power article. (Spoiler, it all comes down to keeping promises.)

I realize, by the way, that all this may feel somewhat cynical and Machiavellian. Am I really just laying out tools for seizing power and shaping hearts, minds, and cultures?

Yeah. I am.

But Machiavelli was wrong. Everybody can have power — it’s not a zero-sum game. In an ideal world, all of our expectations matter to each other, weighted with expertise and benefit rather than money and privilege. The only real problem is dominance, which is different from real power.

Real power grows all power. Dominance demands powerlessness.

Undoing Dominance

Now that we have some ideas and strategies in place, we need to face the elephant in the room. It manifests in patriarchy, capitalism, white supremacy, ableism, heteronormativity, transphobia, and other kinds of hate, but it all shares a common root.

Our global culture is overwhelmed with a belief in dominance.

Your power is other’s belief that helping you will help them. Dominance is when others believe that not helping you will hurt them. In the worst cases, not helping is somehow made impossible.

Dominance is a kind of power, but it’s easy to forget that it’s not the only kind. The most obvious distinction is in the conditional promises employed. Power leverages offers and threats (the future tense of carrots and sticks), while dominance is almost purely threat.

Dominance can be tricky though. Its threats can look like offers if you don’t know what you deserve. “If you work, you can have health insurance.” “If you hide your accent, the jury will be kind.” “If you flirt, you might get a promotion.”

That’s all bullshit, of course. You have a right to life, liberty, and growth. And there’s plenty to go around. The dominance lie, powered by the myth of scarcity, is the root evil in our culture.

Uprooting Toxicity

So dominance has got to go. This is where it all comes together.

Culture is a group’s expectations for each other — the Overton window of accepted options a group member can choose from.

Ours is poisoned by dominance — the accepted expectation that compliance is necessary to avoid pain.

The window needs to be closed on dominance. If a culture stops accepting and therefore expecting dominance, the feedback loop can change.

What is and isn’t accepted can be influenced and changed by social conditioning, courageous acts, and personal power.

We can do this in every group we touch, and we can make it work at scale.

Let’s bring all our strategies together. I’d love to hear more if you get a chance to comment.

Social conditioning:

Carrots: This is the chief tool used to reward and increase good behavior. Basic needs should be satisfied by default, so rewards should go above and beyond to show which behaviors should be repeated. Be sure to reward courageous, culture-shifting behavior that challenges dominance. “Well done. I know that was hard, but you made it clear we don’t tolerate that kind of thing.”

Sticks: These should be used almost exclusively to discourage dominance behavior. Cruelty is scolded. Prisons are abolished. Expectations are high and ignorance is corrected. Focus on the actions, not the people. Draw a clear line and do what it takes to protect people. “Now that you know better, a repeat of that mistake will lose my trust and support.”

Courageous acts:

Beginner’s luck — Challenge dominance behavior whenever you see it, but especially when you’re new. Better to get forgiveness than permission. “Why would you talk to me like that? Is that how people talk to each other here?”

Aggressive Humility — When you hear something that reads as cruelty or dominance behavior, ask questions to force the perpetrator to explain themselves. “What did you mean by that? I don’t get the joke.”

Stack the deck — Organize a strike, or demolish hedge funds with organized buys. Gather community power and make a show of it through letter-writing campaigns and council appearances. Power is in numbers and always has been.

Power at play:

In any group you manage or supervise, make dominance unacceptable. Any display of dominance behavior should be immediately challenged, and challenges to dominance behavior should be visibly rewarded.

In any organization you design, make dominance impossible. This doesn’t mean there aren’t people who specialize in organizing people and making decisions, but it does mean threats aren’t a tool they have. They honestly probably shouldn’t even make any more money than anyone else.